I. Understanding College Athletics

In 2019, the Power Five FBS football conferences generated over $2.9 billion in revenue. The Big Ten Conference generated more than a quarter of that total, leading all over conferences in revenue generated at over $780 million. While the NCAA is in the process of evaluating rule changes that would allow student-athletes to engage in certain sponsorship agreements, student-athlete compensation has historically been limited to academic scholarships. Student-athlete participation is one of the key labor inputs required to produce the NCAA's product: college sports. Since the 1950s, the NCAA has used the terms "amateur" and "student-athletes" to refer to this labor input.

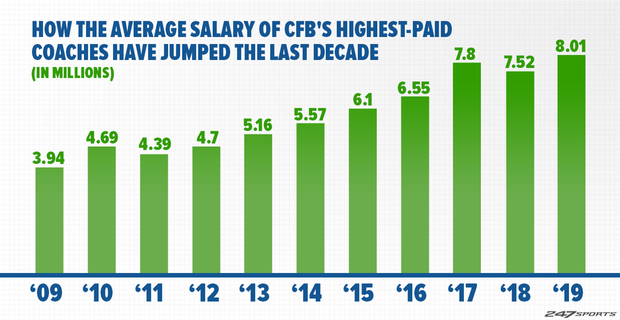

College sports not only provide student-athletes academic scholarships and the opportunity to showcase their athletic abilities, these programs promote a sense of unity throughout school communities and serve as a source of commercial entertainment for those in the stadium stands or watching on their television or mobile devices. As consumer demand for major college sports has grown, so too has the revenue generated through ticket sales and licensing agreements. The revenue generated by sports like FBS Football and Division 1 Men's and Women's Basketball benefit the broader school community by providing funds used to maintain non-revenue sports (generally, only Division 1 Men's and Women's Basketball and FBS Football are referred to as "revenue sports) and facilitate other major projects on campus (such as renovating campus dormitories and academic facilities). But, a significant amount of money is allocated to pay coaches' salaries. Since 2009, the average salary paid to college football's highest paid coaches has nearly tripled.

While both salaries and in-kind payments have increased significantly for coaches, "pay" to student-athletes has remained capped. Currently, student-athletes are compensated only in the form of cost-of-attendance scholarships. NCAA regulations related to amateurism have previously been challenged under federal antitrust law, most notably in NCAA V. Board of Regents, and O'Bannon v. NCAA.

II. The "NIL-Era" and the NCAA's Ability to Regulate

In acknowledgment of the changing landscape of collegiate athletics, the NCAA is now considering rule changes that would deviate significantly from previous regulatory practices employed to govern "amateurism" and promote college athletics. O'Bannon and other legal developments have prompted the NCAA to recognize the need for changing its approach to student-athlete compensation. However, the NCAA insists the distinction between college athletics and professional sports will be eliminated if they are not afforded the ability to govern and limit student-athlete compensation. Maintaining the distinction between college and professional athletics is required to ensure the long-term viability of college sports, but lawmakers, the NCAA, and student-athletes disagree with the correct means of allowing adequate compensation without eliminating this distinction.

Congress is considering numerous proposals outlining the rights and opportunities that should be afforded to student-athletes, and several states including California have already passed legislation doing the same. In 2019, California Governor, Gavin Newsom, signed California's "Fair Pay to Play Act" on LeBron James' television show, allowing student-athletes at California schools to be compensated for certain Name, Image, and Likeness agreements beginning in 2023. This legislationcomes on the heels of O’Bannon v. NCAA, a Ninth Circuit antitrust case from 2015 which paved the way for Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL) legislation. Florida passed NIL legislation after California, but the Florida legislation is scheduled to take effect prior to the 2021 academic year. Accordingly, California lawmakers are attempting to move up the date their legislation takes effect from 2023 to January 2022. Conflicting state legislation has prompted proposals from the NCAA and members of Congress on both sides of the aisle. Federal lawmakers and the NCAA hope to enact legislation that would be applicable to every NCAA student-athlete, regardless of where they attend school and play. By enacting federal rules, all schools will be recruiting and playing on a level field.

III. Alston: "Pay-for-Play" and Sherman Act Arguments

In December 2020, the Supreme Court granted cert in In re NCAA Athletic Grant-in-Aid Cap Antitrust Litig. ("Alston"), agreeing to hear the NCAA’s appeal of the Ninth Circuit’s May 2020 decision. In Alston, the Ninth Circuit ruled that the NCAA could not cap "education-related" compensation for student-athletes, such as computers and musical instruments. The NCAA argues that governing education-related compensation is essential to preventing "pay-for-play" schemes. "Pay-for-play" is the term used to refer to situations in which recruits chose to attend a particular institution based on expected compensation from boosters or others affiliated with the athletic department, rather than making their decision based on academic and athletic goals unrelated to compensation.

As framed by the NCAA, the issue in Alston is “whether the Ninth Circuit erroneously held, in conflict with decisions of other circuits and general antitrust principles, that the NCAA eligibility rules regarding compensation of student-athletes violate federal antitrust law. Analyzing antitrust challenges to NCAA restrictions on student-athlete compensation requires revisiting NCAA v. Board of Regents, a 1984 Supreme Court case discussing antitrust challenges to NCAA restrictions governing television broadcasts of college football games. The NCAA argued that allowing unlimited television broadcasts of certain division one college football games would reduce competition and erode the distinction between collegiate and professional athletics. The Court ultimately held that the challenged restrictions did not promote competition or parity in college football, but not without generally acknowledging the importance of NCAA regulations designed to maintain concepts of amateurism and promote the existence of competitive collegiate athletics. The Ninth Circuit Alston opinion articulated the view that the Board of Regents amateurism discussion is "dicta," but the NCAA argued the Ninth Circuit erred in taking this view. Accordingly, the outcome of the Alston case and legislative developments related to the NCAA's ability to “regulate” NIL and maintain "amateurism" are expected to shape college athletics in the coming years.

The NCAA restrictions at issue in Alston are being challenged under Section 1 of the Sherman Act, which governs restraints of trade. Determining the legality of the NCAA’s restrictions requires testing them under the Rule of Reason, as they do not constitute per se violations of federal antitrust law. The Rule of Reason test consists of three-parts: first, the plaintiff must show the challenged restraint has a substantial anticompetitive effect, second, the burden shifts to the defendant to “show a procompetitive rationale for the restraint;” and third, if steps one and two are satisfied, the burden shifts “back to the plaintiff to demonstrate that the procompetitive efficiencies could be reasonably achieved through less anticompetitive means.” It is generally accepted that the restrictions being challenged satisfy step one, but the legal arguments related to steps two and three merit discussion.

A. Step Two: Market Definition and Cross-Market Justifications

Judge Smith, in his concurring Ninth Circuit opinion, articulated concerns with the Court’s approach to step two. Specifically, Judge Smith disagreed with the view that anticompetitive restraints in one market may be justified by procompetitive benefits in a collateral market. In Alston, the District Court defined the market being restrained as the market for “Student-Athletes’ athletic services,” but indicated in its opinion that the restraints may be justified by procompetitive benefits with regards to “consumer demand for college sports.”

Where the procompetitive benefits proffered by the defendant are realized in a different market than the market allegedly being restrained, they are considered "cross-market" justifications. Judge Smith and others argued that cross-market justifications are inappropriate because the decision to "sacrifice competition in one portion of the economy for greater competition in another portion . . . is a decision that must be made by Congress and not by private forces or by the courts . . . ."

B. Step Three: Less or Least Restrictive Alternative?

At the third step of the Rule of Reason analysis, the District Court rejected two proposed “less restrictive alternatives” offered by petitioners. Despite rejecting the petitioner's proposed alternatives on the basis that they would threaten the distinction between amateur and professional athletics, the Court relied on a judicially created alternative it believed would not “greatly impact” the NCAA’s “latitude to superintend college sports.” However, several economist argue that, if unchallenged, the Ninth Circuit's approach to the Rule of Reason will greatly impact not only the NCAA and collegiate athletics, but all joint venture agreements.

An amicus brief filed in support of the NCAA argues the Court misapplied this step of the analysis. The Court stated “the record support[ed] a much narrower conception of amateurism that still gives rise to procompetitive effects: Not paying student-athletes unlimited payments unrelated to education.” However, the amicus brief argues that “[i]f permitted to stand, the Ninth Circuit’s rule inappropriately would discourage parties from forming procompetitive joint ventures simply because an antitrust lawyer could conceive of a slightly more procompetitive version of the venture in the future.”

By rejecting petitioner's proposed alternative, but relying on one of their own creation, Amici argued the Ninth Circuit had effectively reduced the requisite threshold from "Less Restrictive Alternative" to "Least Restrictive Alternative," and that this distinction broadens the responsibilities of the judiciary to include acting as "quasi-regulators" of business practices. Accordingly, amici argued that a Supreme Court decision in Alston affirming the Ninth Circuit's approach to the Rule of Reason risks disincentivizing procompetitive agreements and other output-producing collaborations by exposing the actors to the potential of treble damages.

IV. Potential Implications of Alston

While Alston will most directly impact college athletics, the decision may provide insight into the approach the Supreme Court will take to other antitrust cases throughout the term. Antitrust lawsuits are expected or pending against Google, Amazon, and Facebook, and a Supreme Court decision upholding the Ninth Circuit's approach to the Rule of Reason may indicate a trend towards more progressive antitrust enforcement. Historically, antitrust jurisprudence has been the story of two dichotomous approaches to legal and economic thought; the Harvard and Chicago Schools. Generally, the Chicago school prioritizes "consumer-welfare" and is more willing to accept anticompetitive restraints that have pro-competitive benefits. In contrast, the Harvard school is grounded in principles of industrial organization. The Harvard approach focuses on a "structure-conduct-performance" paradigm, and is more concerned that large firms in concentrated markets will utilize their market power in ways that harm consumers and reduce competition.

Since the 1970s, the Supreme Court’s Harvard-Chicago-pendulum has swung towards the Chicago approach, demonstrating deference to the perceived ability of large firms to produce more efficient markets. If the Supreme Court upholds the 9th Circuit’s Alston decision, it may indicate a shift back towards Harvard-school influence over antitrust law. The implications discussed above with regards to both college athletics and joint-venture law indicate the importance of the Alston case. Considering the conservative composition of the Supreme Court and the historical tendency of conservative justices to lean towards Chicago-influenced deference towards collaborative conduct in the name of increased output, it may be unlikely that 2021 will mark the beginning of a new Progressive Age of Antitrust.