The Responsibility of Prosecutors to Consider Sex Offense-Related Collateral Consequences

According to the National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Conviction, there are an astonishing 44,778 collateral consequences stemming from criminal convictions. The ubiquity of these consequences mean that a guilty plea rarely involves only probation or a prison sentence; a guilty plea often affects voting rights, employment, housing, public assistance, and citizenship. In the context of sex offenses, a criminal charge and subsequent guilty plea can bar individuals from public and private housing, bar them from homeless shelters, and prohibit them from living in many communities.

That said, a defendant is often ignorant of these possible penalties when pleading guilty. In a criminal justice system overwhelmingly reliant on guilty pleas, a defendant’s ignorance of these penalties runs counter to the constitutional requirement that guilty pleas be voluntary, knowing, and intelligent. So who’s supposed to fill the defendant in? After the Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in Padilla v. Kentucky and its mandate for defense attorneys to advise defendants of immigration consequences, a growing scholarship has tackled the role of defense counsel and judges in advising defendants of the many other consequences. Missing from most of these discussions is a consideration of the responsibility of prosecutors in anticipating collateral consequences, especially the serious consequences resulting from a sex offense conviction. Ignoring the prosecutor leaves out an essential player in the integrity of the criminal justice system, an actor whose decisions arguably have the most effect on which collateral consequences a defendant will face. Prosecutors decide which charges to bring and, thus, which collateral consequences are triggered. In general, prosecutors have broad discretionary authority on which and how many charges to bring against a defendant. But charging an offense is only the first step. The overwhelming majority of convictions result from plea bargaining. Prosecutors have discretion and influence over the terms of the plea bargain, the offense to which a defendant pleads guilty, and thus, the ensuing collateral consequences. This discretion is not boundless, of course: as Robert M. A. Johnson, former President of the National District Attorneys Association, has said, “[C]riminal justice standards and court decisions…call on prosecutors to seek justice, not merely to convict offenders.”

When imagining how a prosecutor can incorporate sex offense-related collateral consequences into their discretionary charging decisions and plea negotiations, we already have a case study in the immigration context, thanks to Padilla. Under Padilla, defense counsel is required to contemplate the immigration consequences her client may incur, making the potentiality of deportation a factor in the plea negotiation. The defendant and the defense attorney often want to avoid the greater punishment of deportation while a prosecutor typically wants the efficiency of getting the guilty plea and avoiding trial. Because there are multiple charges that fit the alleged crime, the prosecutor can use her discretion to choose charges that satisfy her responsibility to render justice while sidestepping a disproportionately harsh deportation. This post-Padilla relationship between defense and prosecution is borne out in a survey of prosecutors working in Brooklyn, New York. As one respondent to the survey said, “[T]he prosecutor has to determine if the promised sentence, along with the likely collateral consequence, is proportional to the offense that the defendant is pleading to.” The defendant then must decide whether to waive his trial rights and plead guilty to a lesser offense which avoids deportation or to go to trial for the original deportation-triggering offense. The darker side of this justice-oriented consideration of immigration consequences is the coercive effect on defendants to plead guilty simply to avoid deportation.

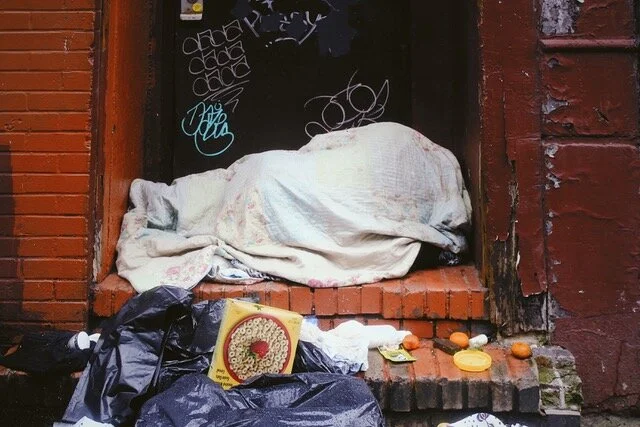

“In many cases, the collateral consequence of a sex offense conviction means homelessness for an individual, a potentially graver punishment than the prison time he will serve.”

Whether a Padilla-like mandate for advisals about sex offense-related housing collateral consequences will lead to similar effects on prosecutors in their charging decisions and plea-bargaining strategies is not entirely clear. There are critical differences between how convictions trigger immigration consequences and how they trigger sex offense-related housing consequences. For instance, under federal immigration law, not all theft offenses are deportable offenses. Only felony theft and burglary offenses trigger possible deportation. In considering which charges to bring, a prosecutor may have discretion to charge a misdemeanor theft or trespass offense or to negotiate a guilty plea to the misdemeanor charge, thereby serving justice and avoiding incommensurate punishment for the crime. However, for sex offense-related consequences, a prosecutor generally has less latitude to avoid a severe collateral housing consequence. In New York, for instance, a conviction of almost every sex offense under the penal laws triggers the consequence of public registration. Public registration in turn limits an individual’s access to public housing. Public registration also opens up the likelihood of landlord discrimination in the housing market. The only two offenses not swept into the registration requirement are the misdemeanor offenses of “forcible touching” and “sexual abuse in the third degree.” By making almost every sex offense a trigger, New York’s registration laws leave fewer options for a prosecutor to choose a less serious charge to apply to an incident. However, making prosecutors more cognizant of even fewer options in their charging and plea bargaining decisions is still worthwhile.

More importantly, the impact of Padilla advisals reaches far beyond defense attorneys and judges. As illustrated post-Padilla, prosecutors now routinely integrate immigration consequences into their charging decisions and plea negotiations. This change occurred without a Supreme Court mandate specific to prosecutors. The Supreme Court should extend its holding in Padilla and expand the advisals of defense counsel and judges to include sex offense-related collateral consequences; these expanded responsibilities of defense counsel and judges will inevitably influence the prosecutor’s professional duty to “seek justice…not merely convict.”

The collateral consequences that a defendant would incur deserve the consideration of prosecutors. In many cases, the collateral consequence of a sex offense conviction means homelessness for an individual, a potentially graver punishment than the prison time he will serve. For that reason, prosecutors, along with defense counsel and judges, must all consider the unjust effects of these sex offense-related consequences when charging an offense and negotiating a plea. The Supreme Court should extend Padilla and do its part to ensure that defendants are fully aware when they plea and that punishment is just.